Uncompensated Care Costs In Hospitals with NICUs

(download white paper with references)

- Medicaid is the single largest payor for hospitalized children

- Cost to care for preterm infants is disproportionately high compared to full term infants due to long lengths of stay

- Preterm infants are more likely to be incubated while in the hospital

- Medicaid reimbursements fall below hospital costs, especially for neonatal patients

- On average, Medicaid reimburses children’s hospitals only 80\% of the cost of care provided

- The uncompensated costs are a major concern for hospital administration

- A mechanism to safely reduce the length of stay for preterm infants would reduce Medicaid shortfalls

Role of Medicaid

Medicare provides health care coverage for senior citizens and some disabled Americans while Medicaid provides health care coverage to low-income families and individuals. Another CMS program provides additional payments to Disproportionate Share Hospitals (DSH) that shoulder a higher level of costly-to-treat Medicaid patients. DSH payments help hospitals recover uncompensated costs of both Medicaid-insured and uninsured patients.

While some children have commercial insurance and others are not covered by either Medicaid or commercial insurance, Medicaid is the single largest payer for hospitalized children. The proportion of hospital stays for children covered by Medicaid has increased over time, and the proportion covered by private insurance has decreased.

Medicaid uncompensated costs

While Medicaid and DSH payments defray some of the costs associated with the care of hospitalized patients, hospitals are left with high levels of uncompensated costs. Broadly, the annual underpayment for Medicare is $75 billion and for Medicaid is $25 billion.

These Medicaid shortfalls disproportionately affect hospitals caring for children. The higher proportion of Medicaid patients in freestanding children’s hospitals (FSCHs) concentrate Medicaid shortfalls. FSCHs had a higher median number of Medicaid-insured discharges compared to non-children’s teaching hospitals and non-children’s, non-teaching hospitals, concentrating the Medicaid shortfalls.

The median annual net loss for all hospitals in the Kids Inpatient Database (KID) attributable to Medicaid-insured patients has been reported at $28,749,182 (2009 dollars). This is likely an underestimation of losses due to the increase in enrollment of children in Medicaid since 2009. Focusing on FSCHs within KID found losses in excess of $30 million per hospital, although this was reduced by about half when including DSH payments. Medicaid pays 88 cents on the dollar for all hospital care costs but only 80 cents on the dollar for FSCH care costs.

Disproportionate Medicaid losses with preterm infants

More specifically, neonatal intensive care units (NICUs) are susceptible to Medicaid uncompensated costs. Treatment expenses are highly concentrated for preterm infants, especially LBW and VLBW patients most often treated in NICUs and that would tend to be hospitalized for long periods. Nearly three-fourths of hospital stays for children and more than half of all hospital costs for children were for newborns and infants. LBW and VLBW births represent about 9% of hospitalizations but account for 43% of total costs. This is the patient population that would likely be incubated.

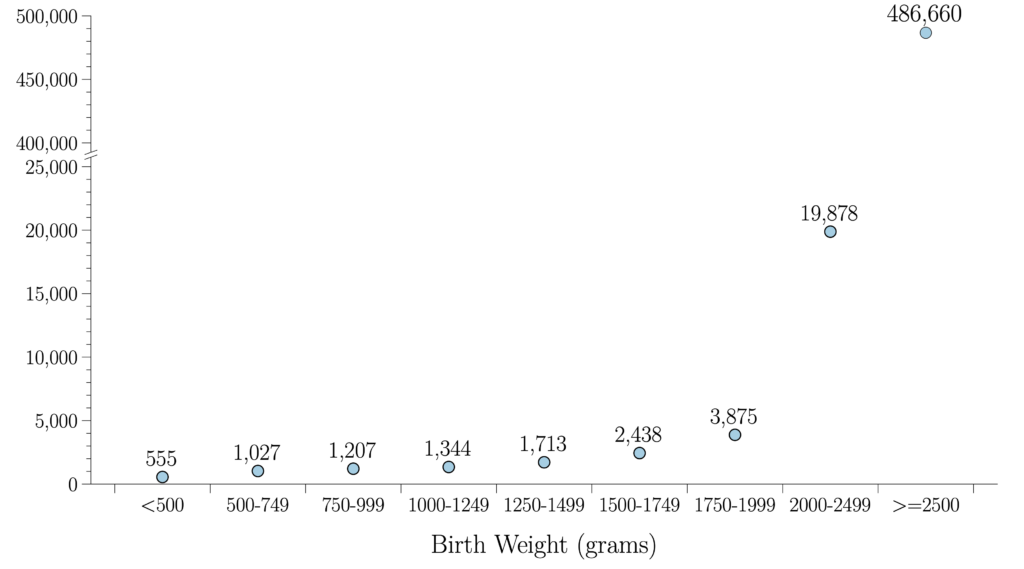

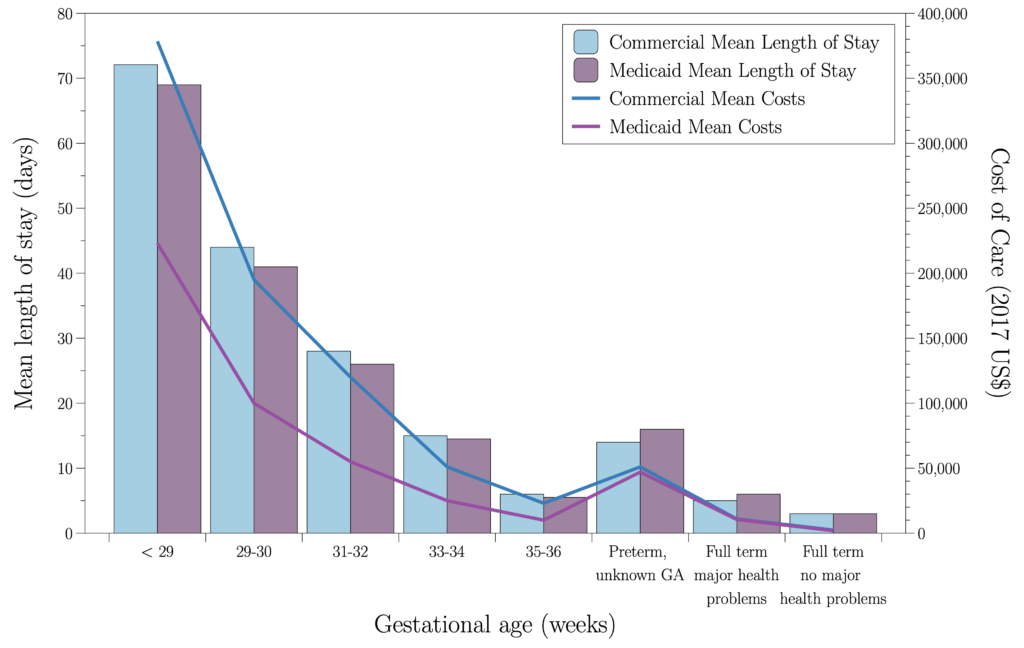

Among live births, full-term infants weighing greater than 2,500 grams make up the vast majority compared to LBW and VLBW infants (Fig. \ref{fig:Total_Num_by_BW}). However, the length of stay and the cost of care rise exponentially with lower birthweights (see figure below).

The lower the birthweight, the more likely the patient is to be incubated in the NICU. There is little difference between the length of stay for patients with commercial insurance compared with Medicaid-insured patients (see figure below), likely due to a rationing of care associated with the lower reimbursements expected by hospitals. Shortening the length of stay is a means of lowering the cost of care.

In the first two years of life, total healthcare charges for extremely preterm (≤28 weeks gestational age) infants are significantly higher than for infants born at more than 28 weeks gestational age; total all-cause healthcare charges in 2018 US dollars were 5.4 times higher in the extremely preterm cohort ($843,499) than in the mature/late-premature cohort ($158,430), and 2.3 times higher than in the very preterm cohort ($379,581).

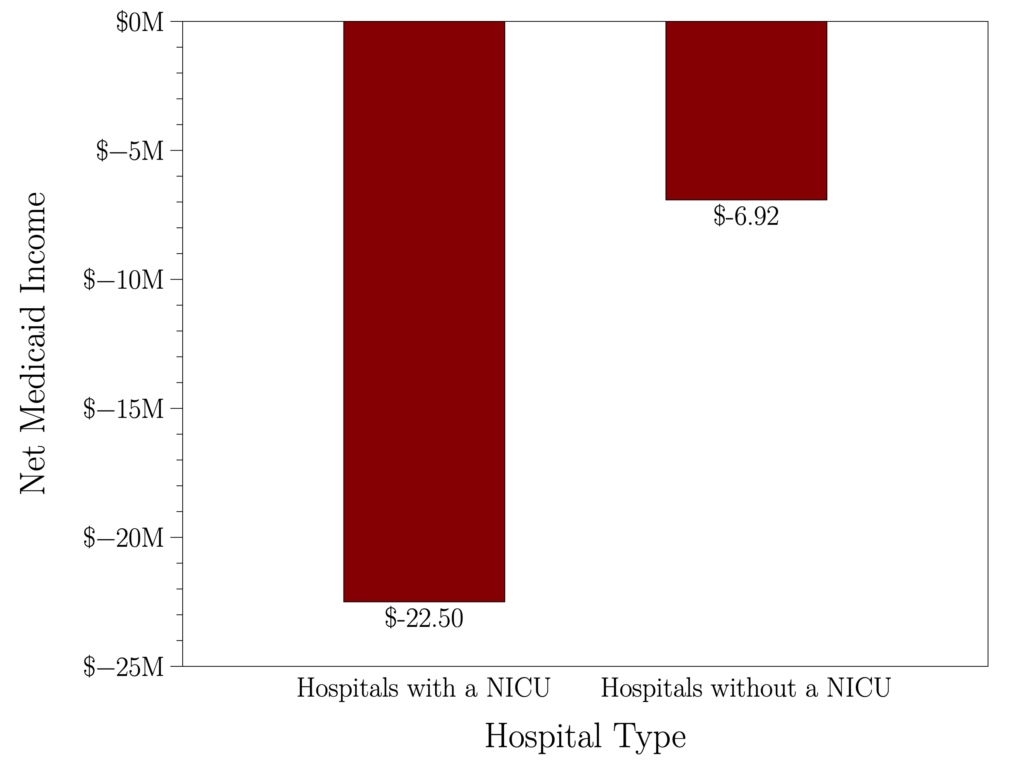

An analysis of the DSH database of every hospital receiving DSH payments shows that the average annual per hospital uncompensated care costs including both Medicaid and DSH payments was $22.50 million (4.5% of all hospital care costs) for hospitals containing a NICU and $6.92 million (5.0% of all hospital care costs) for hospitals without a NICU (see figure below).

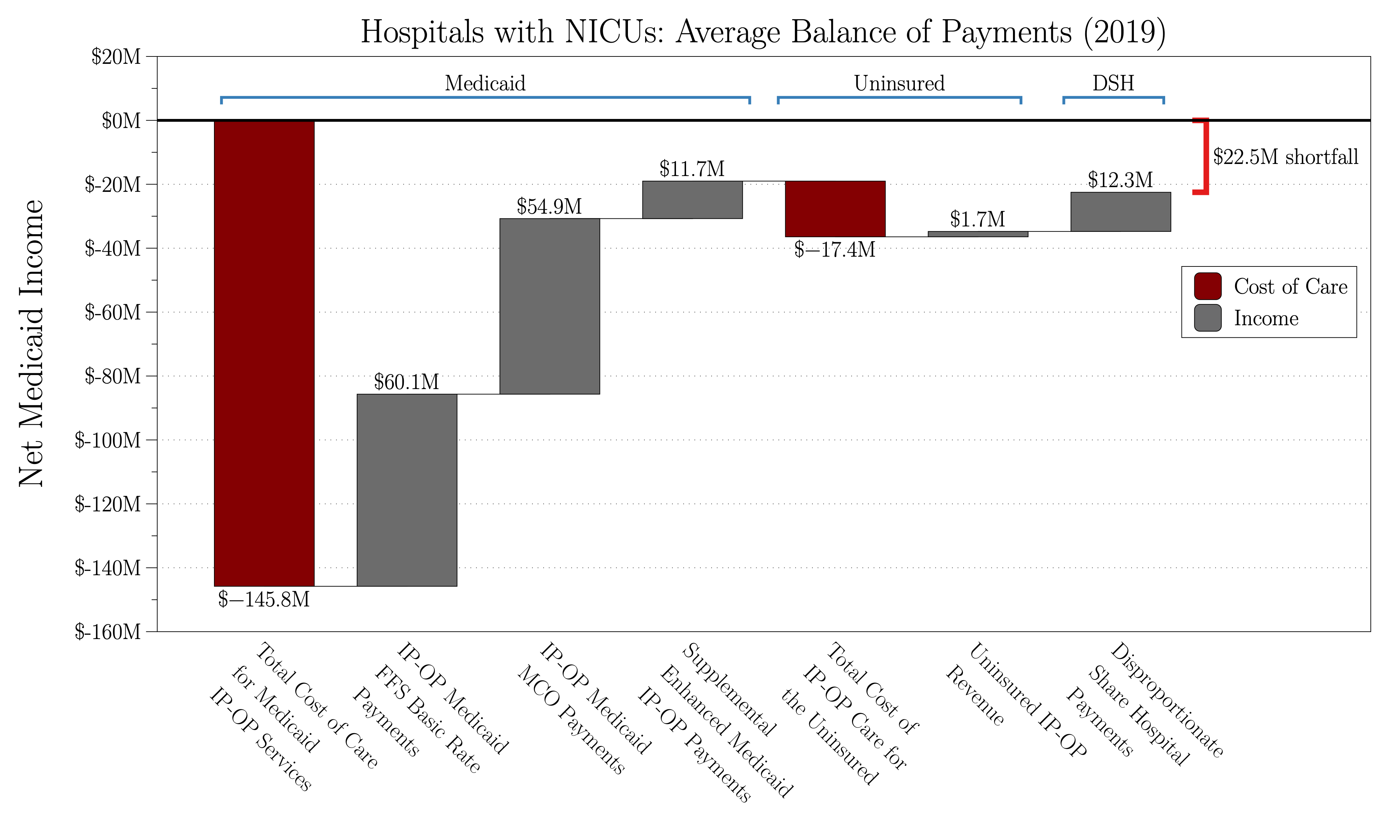

The walk-through of the average costs to treat uninsured and Medicaid patients and the compensation provided for these patients (see figure below) shows the origins of the imbalance.

Summary

Preterm LBW and VLBW patients are likely to be treated in NICU incubators. These patients are most likely Medicaid-insured and represent a disproportionate share of cost to care and therefore contribute greatly to hospitals’ financial shortfalls.

Average annual financial losses of $22.50 million from inadequate Medicaid coverage, disproportionately associated with the care of preterm children, remain a major concern for health officials and policymakers.

A seemingly modest improvement in the safe reduction of length of stay of these patients can have a significant bottom-line benefit to the hospital. A noise reduction-equipped infant incubator that was able to improve the length of stay by only one day could result in avoiding over $1.1 million losses annually in the NICU alone. This is based on the daily NICU costs of a very preterm infant (≤ 33 weeks gestational age) of $8,600 conservatively estimated for a hospital having 20 incubators, an 80% census, and a rate of 8 infants per incubator per year.

The link between sleep disruption in the intensive care unit (ICU) and increased morbidity and mortality in the critically ill patients is well-documented. Development and deployment of active noise reduction technology in other hospital care areas has the potential to reduce cost of care and limit hospital financial losses further.